How will future readers perceive our words?

How do written words lead to empathic growth?

Chiaet’s explanation for this is that literary fiction focuses more on the psychology of characters and their relationships, while popular fiction is formulaic, portraying situations that might be a “roller-coaster ride of emotions and exciting experiences,”but which also feed into the reader’s expectations of others. In other words, it does not increase their capacity to empathize.

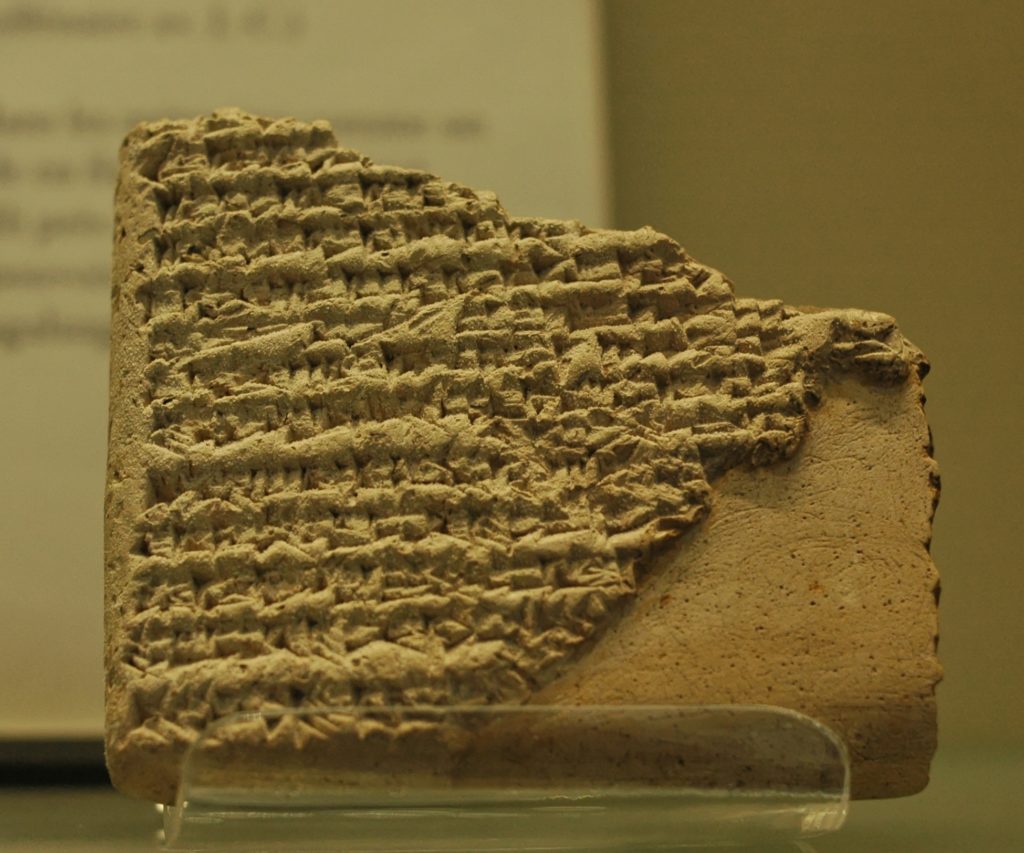

How did ancient people use the written word?

Photo credit: Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Photo credit: Louvre Museum, Public domain, via Wikimedia CommonsLater, the ancient Egyptians developed three types of scripts—hieratic, sekh shat and hieroglyphic—for sacred writings, ordinary records, and monument inscriptions. Hieratic was used to tell the stories of gods, goddesses and pharaohs. Sekh shat (also known as demotic script) was used for counting crops and animals, letter-writing and governmental records. Strictly speaking, hieroglyphs were pictograms found on temple walls or public monuments, such as the Pyramids.

How do modern people use the written word?

Today, written words are used in more ways than ancient people ever conceived. At their best, they entertain, educate, inspire, counsel and encourage us. The influence of the written word begins early in childhood and has lasting effects. My mother, for example, never took education for granted. She grew up in World War II Germany, when her schooling was literally interrupted by bombs falling from the sky. Library books were mostly not an option, as they were not free to borrow. Because of this, she appreciated the benefits of a public school education and took seriously the written parent/teacher reports she received about the academic progress of her four children. She encouraged all of us to make the most of our schooling. “Nobody can take your education away from you,” she told us repeatedly from the perspective of a naturalized citizen who was proud to be American. Of course, this is not so true for many black or brown American students who may not have the same educational opportunities as others. But my mother’s intent was to make sure we appreciated and used the education we were provided at no cost.

My mother was also concerned with our friendships. During World War II, her classmates joined the Hitler Youth program, something she was not, as the daughter of a Lutheran minister, allowed to do. She was too young to understand the ramifications at the time, but as an adult, she realized what might have transpired if she had been allowed to join. My mother used to advise us, “Tell me with whom you go, and I’ll tell you who you are.” Our son became familiar with these words which are now framed and have a special place in our family room.

For people involved in faith, politics, government, science, business or the arts, written words can connect, advertise, negotiate, reconcile and effect change. But they can also denigrate, discourage, confuse, and divide us; they can incite fear, hate and violence. I cannot think, for example, of a more divisive Presidential election than the one that just took place.

How do we preserve today’s written words?

For better or worse, written words—and for that matter, spoken ones—have lasting consequences.

Sources for book quotes at the beginning of this post:

- Quote #1 – The Left Hand of Darkness, by Ursula K. LeGuin (winner of the HUGO and NEBULA Awards for Best Science Fiction Novel of the Year)

- Quote #2 – All the Light We Cannot See, by Anthony Doerr (National Book Award Finalist and 10 Best Books, The New York Times Book Review 2014)

Resources:

- Novel Finding: Reading Literary Fiction Improves Empathy, https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/novel-finding-reading-literary-fiction-improves-empathy/

- The Evolution of Writing, https://sites.utexas.edu/dsb/files/2014/01/evolution_writing.pdf

- “Writing,” Ancient Egypt, http://www.ancientegypt.co.uk/writing/home.html

- “Hieroglyphic writing,”Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/topic/hieroglyphic-writing

- John F. Kennedy’s Inaugural Address, https://www.ushistory.org/documents/ask-not.htm

- Open Library (Internet Archive), https://openlibrary.org/

- Wayback Machine (Internet Archive), https://web.archive.org/

© 2021 Judy Nolan. All rights reserved.